Predicting Asteroid's Position: Special Case

There are a few special cases where simple methods can predict new positions. These special cases are all due to the elliptical symmetry of an orbit; the semiorbit above the major axis mirrors the semiorbit below the major axis. These include following scenarios.

Orbit Multiples. This is by far the simplest method. One can readily predict orbital positions for one, two or more periods in the future (or past). For example, assume that the period, T, for Apollo's orbit is exactly 650 days. (Apollo is a Near Earth Asteroid, NEA). Then, position of Apollo for 650 days from now will be at the same orbital position.

Recall Kepler's Third Law, knowing an orbit's semimajor axis, a, is sufficient to compute orbit's period, T. You don't have to know e, eccentricity, or any other value about the specific orbit under study.

If we assume that Apollo passes q, its perihelion, on April 11, 2009, then we can safely predict that it will come back to q 650 days later on Jan 20, 2011.

Another example: Consider another point in Apollo's orbit. To arrive at 45° past q will take Apollo 21 more days (arriving March 1, 2009); from that point, we can safely predict another arrival at this new point in another orbital cycle. Thus, we predict that at Mar 1, 20o9 plus T (plus 650 days = Feb 10, 2011), Apollo will once again arrive at 45° past q.

This leads us to a simple brute force method where observations can be made daily throughout an asteroid's orbit; then, position predictions can be made accurately for any of those positions and interpolated for times between those exact daily times. For example, we could make 650 daily observations of Apollo from start to stop of its orbit, then forecast future positions accordingly.

The downside of orbital multiples, there are an infinity of positions impossible to make observations to accommodate all of them. A more elegant method would involve a procedure to calculate positions for any time, then use observations to confirm.

Semiorbit Multiples. We can also predict positions for even multiples of semiorbits from either q or Q(for Apollo, T/2 = 325 days). For example, 325 days from perihelion, q, Apollo will progress 180° around the orbit to the aphelion, Q. Unfortunately, this proportionality is very specific and does not extend to other half cycles nor to other fractions.

Q to q. The elliptical orbit from q (perihelion) to Q (aphelion) is exactly 180° and takes exactly half the period, T/2.

Q to q. The elliptical orbit from q (perihelion) to Q (aphelion) is exactly 180° and takes exactly half the period, T/2.- q to Q. Of course, the remaining half of the orbit will also take T/2. This is due to the limited symmetry of an ellipse; major axis divides ellipse into two parts which are equal in size and shape.

- All other 180° portions of the orbit have elapsed time values which differ from T/2.

- Similarly, most (perhaps all) 120° segments do not take exactly T/3. This lack of proportionality applies to all fractions of the orbit.

Axial Symmetry. Special cases of simple time predictions are due to the fact that elliptical orbits are symmetrical about the major axis which divides the orbit into two equal but opposite semiorbits.

Orbital speeds have an inverse relationship with their radius, distance from Sol, our sun. Speeds increase as the radius decreases until speeds achieve a maximum at the closest point to the sun; this point is the perihelion, often designated, q (lower case). On the other hand, orbital speeds decrease as the orbital radius increases; they decrease until they reach their minimum at farthest distance from Sol, aphelion, Q (upper case Q). This phenomena enables us to make simple predictions according to angular distance from either q or Q.

Since an orbit's perihelion is an orbit's unique position, it's used as starting point to measure angular progress around the orbit. Counter clockwise. Thus, ray from Sun, S, to perihelion, q, is normally given as 0°. Any subsequent angular position iss called the asteroid's "true anomaly" as the difference from reference ray, S-q. (True anomaly normally written as Greek letter "nu", ν.

Since an orbit's perihelion is an orbit's unique position, it's used as starting point to measure angular progress around the orbit. Counter clockwise. Thus, ray from Sun, S, to perihelion, q, is normally given as 0°. Any subsequent angular position iss called the asteroid's "true anomaly" as the difference from reference ray, S-q. (True anomaly normally written as Greek letter "nu", ν.

We normally measure angles and times from q, perihelion, thus, reverse symmetry could enable us to determine previous passings. Recall the anomaly from q is usually expressed as the angle, ν, true anomaly. If we determine that Apollo's ν is 15° and it took 6.4 days to get there; then, we can surmise for 15° prior to q (ν = 345°) Apollo was there at 6.4 days, or it took Apollo 6.4 days to reach q from 345°. This works for any angle, and it also works for Q (ν = 180°) as reference point.

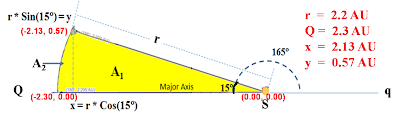

For example, the figure at left demonstrates a symmetry about Apollo's Q, aphelion. Specifically, figures show that Apollo takes 75.3 days to orbit from 165° to 180°. Once we measure the time from 15° prior to semimajor axis, then we can forecase same amount of time to progress another 15°.

For example, the figure at left demonstrates a symmetry about Apollo's Q, aphelion. Specifically, figures show that Apollo takes 75.3 days to orbit from 165° to 180°. Once we measure the time from 15° prior to semimajor axis, then we can forecase same amount of time to progress another 15°.

For above special cases, examples can be observed from a diagram of Apollo's orbit.

Tycho (1546-1601) was a Danish noble, who practiced astronomy rather than politics. Granted the island of Hven in 1576 by Frederick II, he established Uraniborg, an observatory containing large, accurate instruments. On 19 April 1559. Tycho began his studies at the University of Copenhagen. Following the wishes of his uncle, he studied law and several other subjects including astronomy. However, the accurate prediction of the actual eclipse of 21 August 1560 so impressed him that he at once concentrated on astronomy. He purchased an ephemeris and books such as Sacrobosco's Tractatus de Sphaera, Apianus' Cosmographia seu descriptio totius orbis and Regiomontanus' De triangulis omnimodis. His foster parents decided that he should gain experience abroad; and in February 1562, he went to the University of Leipzig. His official studies included classical languages and culture, but he had bought his astronomy books with him together with Dürer's constellation maps. By August 1563, still at the University of Leipzig, he began recording observations. His second was a conjunction of Jupiter and Saturn which proved significant for Tycho's subsequent career because other contemporary tables gave incorrect dates for this event. Ptolemy's table was off by nearly a month and even Copernicus' was off by days. Tycho, with typical teenage confidence, thought he could do better, and he proved to be right! Tycho then studied astronomy with Bartholomew Schultz at Leipzig who taught him some techniques to improve accuracy. Tycho knew that accurate observations required good instruments, and he began to acquire them. Tycho returned home in May 1565; and in the following month, his uncle, Jorgen, lost his life while rescuing the King. His father, who now commanded Helsingborg Castle, and mother assumed responsibility for the young man who was still under eighteen. The appearance in 1572 of a "new star" (in fact, a supernova) prompted Tycho's first publication in 1573. In 1574, he gave some lectures on astronomy at the University of Copenhagen. At this time, he believed the world-system of Copernicus to be mathematically superior to that of Ptolemy, but he still considered the Copernicus model to be physically absurd. In 1576, his permanent relocation to Basle, which he considered the most suitable place for him to continue his astronomical studies, was forestalled by King Frederick II, who offered the island of Hven in the Danish Sound. With generous royal support, Tycho constructed there a domicile and observatory which he called Uraniborg, and developed a range of instruments of remarkable size and precision. With numerous assistants and students, he observed comets, stars, and planets. While Tycho is best remembered for bequeathing a wealth of astronomical data to Kepler, he is also remembered for following colorful incident. In 1566, Tycho was at the university in Wittenberg. While there, he was involved in duel with another Danish student and had part of his nose cut off. As a consequence, Tycho developed an additional interest in medicine and alchemy. After his return home in April 1567 he had an artificial nose made from silver and gold. Unfortunately, he was disfigured for life, and his portraits show this disfigurement which was almost certainly worse than what the artists portrayed. |

In 1584, he needed more room to house all his increasing inventory of large, accurate instruments; therefore, Tycho built Stjerneborg adjacent to Uraniborg. At this time, Tycho was most active in producing major new instruments.

Accuracy from above instruments fell mostly between about 0.5' and 1.0', that is, about the accuracy of the standard used for comparison. Thus, Kepler believed that Tycho's observations could be trusted to better than two minutes of arc. |

We've demonstrated the straightforward process of determining area of a Sun anchored segment adjacent immediately above the major axis. We propose that same process can determine area of any similar segment below the major axis. Since the dimensions of these two segments must be equal (if they're not, then the orbit is not elliptical); then the areas must also be equal. Thus, according to Kepler's Second Law, the orbital transit times must also be equal.

We've demonstrated the straightforward process of determining area of a Sun anchored segment adjacent immediately above the major axis. We propose that same process can determine area of any similar segment below the major axis. Since the dimensions of these two segments must be equal (if they're not, then the orbit is not elliptical); then the areas must also be equal. Thus, according to Kepler's Second Law, the orbital transit times must also be equal.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home